by Jeff Giles

from US Rolling Stone, August 9, 1990

About fifteen minutes outside Belfast, Hothouse Flowers' van comes upon one of Northern Ireland's makeshift military blockades. It is one o'clock in the morning, and the Dublin group - whose first record, 1988's People, was the most successful debut in Irish history - is returning home from a particularly joyous gig. Now, with a soldier approaching, the mood in the van has turned tense. "Here we go," the driver says, fishing around for identification.

Fortunately, after a few terse preliminaries, it becomes clear that the soldier recognises the band. "Where have you been playing?" he asks Liam O'Maonlai, the group's soft-spoken twenty-five-year-old singer and pianist.

"The Belfast Opera House," O'Maonlai tells him.

"How was it?"

O'Maonlai grins and shakes his head. "You should have been there," he says.

It's true. Tonight, in one of the first shows of a worldwide tour for their second album, Home, Hothouse Flowers played for two and a half hours to a more or less perpetual standing ovation. The stage itself - dominated by three psychedelic-patterned platforms - gave the whole affair the look of a Sixties TV show. The music, however, bridged several decades: Celtic soul a la Van Morrison and rock & roll a la Bruce Springsteen, as well as strains of traditional Irish music, country and gospel. A barefoot O'Maonlai played a vigorous kick-the-stool-over kind of piano and, with twenty-four-year-old guitarist Fiachna O'Braonain, ventured into the crowd to whip up some house-shaking call and response. For a night, the opera house - an ornate wedding cake of a building - looked a lot like a Baptist church.

Now, as the van moves away from the Blockade, O'Maonlai says, "The North is a special place to play. Bands just don't play there as regularly as they do the rest of country, because it's got a name for being a violent place. So the people are starved, in a way.

Asked how he had felt staying in a Belfast hotel that has been repeatedly bombed in recent years, O'Maonlai says, "If I drown, I drown. If I'm shot, I'm shot. It's pointless worrying about it." He pauses, then goes on: "In America, people come up and try to get on my good side by saying, 'Are you Protestant or Catholic?' They wait for me to say, 'Catholic,' and then they launch into their pro-IRA bit. Now I just say, 'I'm not telling you, because I'm not getting involved. Nobody's right anymore.'"

O'Maonlai is quiet for a moment. Drummer Jerry Fehily, who's sitting in the back of the vanand listening to a tape of tonight's concert on his Walkman, takes the opportunity to tease him about getting carried away during the show. "'She Moved Through the Fair' was a quarter of an hour long, Liam," he says, rather loudly. "Pure wank."

O'Maonlai smiles. "Yeah, that's a nice one," he says. "I like to let that one go on a bit."

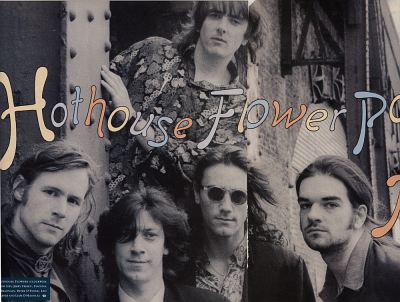

By three o'clock in the morning, the last of the Flowers - who also include bassist Peter O'Toole, 25, and jazz-trained saxophonist Leo Barnes, 34 - have been dropped off at their homes in Dublin. It is here that, after a year of college, O'Maonlai and O'Braonain began working as street musicians in 1985. They had met as children in a Gaelic-speaking school - the pair still occasionally converse and give interviews in the ancient language - where they studied, among other things, traditional folk instruments. (Hothouse Flowers' arsenal includes bouzouki, mandolin, tin whistle and the bodhran - a goat-skinned drum.)

Performing on the street as the Incomparablee Benzini Brothers, O'Maonlai and O'Braonain were soon joined by Peter O'Toole, who had left school at sixteen and gone on to deliver bread, make fiddles and work as a lumberjack. "We'd been in the same band before," O'Toole says of O'Maonlai, "but we'd never actually met. It was that sort of band - there were loads of people."

Of the Benzini Brothers' sidewalk set, O'Braonain says, "We just did a lot of bad songs, and we used to do dances. We did an antismoking song. We did a very fast, manic version of 'Kansas city.' I think most of what we did was quite fast and manic. When we forgot the lyrics, we'd just get everybody to sing along. It was a brilliant summer."

Before long, the Benzini Brothers had won a street-entertainer award, and Hothouse Flowers was formed. (The band would soon be singled out by ROLLING STONE as "the hottest unsigned band in Europe.")

In September," O'Braonain says, "I went back to school with a heavy heart. I didn't go to any lectures or tutorials, and it was drawn to the attention of the deans. So I went in, and they gave me a two-year leave of absence, which was great. I felt quite funny, though. You know, 'I'm sorry I haven't gone to any of my lectures, but I'm in a rock band.'"

The day after the Belfast show, Hothouse Flowers are back in their van and headed toward Cork for a television appearance. O'Maonlai, who left college along with O'Braonain, is playing tin whistle. Barnes is reading a biography of James Joyce's wife, Nora. O'Toole and his girlfriend are looking at each other through binoculars and giggling. A few hours into the road trip - just when everyone seems about to go stir crazy - O'Maonlai gestures at the rolling countryside and says ominously, "'The Plains of Kildare.'". The entire group breaks into song.

When things have quieted down again, O'Maonlai begins talking about U2's Bono, who, in 1986, saw Hothouse Flowers on Irish television and called them up to arrange a meeting. "Basically," O'Maonlai remembers, "he just wanted to say, 'I know this sounds silly and you probably think I'm an awful idiot - the gall I have - but I think your music is brilliant. If there's any advice I can give you, let me know.'"

Hothouse Flowers eventually released released a single called "Love Don't Work This Way" on U2's own label, Mother Records. It wouldn't be long before Sinead O'Connor would be telling interviewers that bands couldn't make it out of Dublin without kissing Bono's ring, and she'd have a few words to say about Hothouse Flowers in particular. "She called Liam a poser," O'Braonain says. "And she said she just didn't like our music, which is fair enough. It's not something we're going to hold against her."

O'Braonain writes off O'Connor's comments as "the bravura of a twenty-year-old" and says the band doesn't feel a part of any particular "scene." A recent Face article, however, made Dublin out to be one big, neo-hippie hoedown, and Hothouse Flowers would seem a perfect case in point. O'Maonlai describes himself as looking "longhaired and lackadaisical." His lyrics, moreover, have a spiritual slant and run along the lines of "Long as you know love is everything, the world is wide." Still, the members of Hothouse Flowers, most of whom are vegetarians, say the notion of a widespread hippie revival in Dublin is just "wishful thinking."

After releasing the Mother single, Hothouse Flowers signed with PolyGram. People, their debut album - made up entirely of originals by O'Maonlai, O'Braonain and O'Toole - found its way to the top of the Irish charts within a week and reached Number Two in England. A video for the album's first U.S. single, "Don't Go" - a life-affirming number marked by its urgent vocal and its brisk piano runs - was aired before 200 million television viewers on a Eurovision Song Contest special, and the song became a hit all over Europe.

"Don't Go," like much of Hothouse Flowers' music, brings Springsteen to mind. The band members, however, have only a passing knowledge of anything pre-Tunnel of Love.

"I remember listening to some album," O'Braonain says, as the van nears Cork. "Greetings from some park."

"There's a song called 'Born to Run'," O'Toole says. "There's an album called Born to Run."

The Flowers cite as their influences Bob Dylan, the Chieftains, the Waterboys and Joe Cocker, among others. But traditional music often proves the most irresistible. At the moment the Hothouse Flowers' van arrives in Cork, the band members are singing an Irish sailing ditty at the top of their lungs.

Hothouse Flowers began recording Home in November of 1988. By spring of the following year, however, they were interrupted: People had shown an unexpected staying power, and the band members were called away to tour Japan, as well as to tour for a second time in the States, where they'd graduated from playing clubs to playing theaters.

Hothouse Flowers' stateside visits included a couple of unexpected trips to recording studios. During a stay in Los Angeles, some of the Flowers did session work for the first Indigo Girls album. And on a stop in New Orleans, the band did some impromptu recording at Daniel Lanois's studio. Dylan was around at the time - Lanois was in the midst of producing Oh Mercy - but the group never managed to meet him. "He didn't get up that early," O'Braonain says.

Although one of the songs from the New Orleans sessions made it onto Home - a spare, plaintive track called "Shut Up and Listen" - Lanois, who was gearing up for his own tour, had to decline a request to produce the record. The Flowers returned to Dublin and found that a lot of fans were getting impatient. "We were on the road a fuck of a lot longer than we expected to be," O'Braonain says. "And we're young - we needed a little recovery time."

The band spent part of that recovery time playing at after-hours jam sessions. "Around the city," O'Toole says, "everybody would ask, 'What's happening with the new album? What are you doing?' Whereas we could go into these sessions and nobody would wonder what we were doing. They'd just say, 'This is in the key of C.' And we'd sit down and play."

Home, which was finally released in June, about two years after People, is even more diverse than its predecessor. It includes - along with the spirited up-with-people single "Give It Up" - a cover of Johnny Nash's "I Can See Clearly Now" and a Gaelic traditional, sung a cappella, called "Seoladh na nGamhna." "It means 'The Herding of the Calves,'" O'Braonain says. "It's a love song, although the fact that it's called 'The Herding of the Calves' may sound a bit unromantic."

Following a sound check for tomorrow's television show, which will also feature K.D. Lang, the Flowers take up residency in a nearby pub. Before long, they're singing Ry Cooder's "Jesus on the Mainline." O'Maonlai is leading the chorus. Even Leo Barnes, who brings a pleasant measure of cynicism to what is otherwise a quite modest, kind-spirited group, is contributing in his own way. Every time the group sings the line "Tell him what you want," Barnes cups his hands around his mouth and shouts, "A pint of Guinness!"

"Any little bits of gospel I've heard have always rung true to me," O'Maonlai says, between numbers. "It's managed to reach the same level of power as traditional music. And if anything does that, then I think some part of me takes it in, locks it up and says, 'This is good for you.'"

Of Hothouse Flowers' music, which somehow combines the sailing ditties and the gospel, O'Maonlai says, "It's not fashionable, I think. It's got a bit of timelessness, so we get a good spread of audience - people of all ages." He pauses as the group starts in on "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot." "A seventy-year-old woman came up to us when we were down in Kerry," he says, "and she insisted on giving us all a kiss because of the good work we were doing."